I write today out of grief and love. I have always turned to literature when things are truly bleak. Still Life transported me to glorious Florence, and as E.M. Forster makes an actual appearance, back in time to when I first read A Room With a View, an experience that brought light into my life during a dark time. I have never been to Florence, despite two aborted attempts to visit, but I feel as though I can picture the way the light must look in Tuscany, thanks to literature. Still Life is about grief and love and the inextricably intertwined threads these emotions weave through out lives.

I have never been particularly patriotic, but I have been an optimist, believing that more rights would be gained, never that I would see them lost. My heart is broken. I find myself in a deep depression, and yet there’s still a creative spark. Still Life helped me see it this week. So, thank you to Sarah Winman and to the perfect timing of my library.

This novel follows many characters for many years, from the 1940s to the end of the 1970s, with a jaunt back to the early years of the twentieth century. Ulysses Temper is the novel’s protagonist, and we meet him as a young man in Florence. He’s part of the British forces helping to chase the Germans out of Italy when he meets Evelyn Skinner, an art critic in her sixties. Together, they experience both the discovery of an incredible painting hidden in a cellar and a bombing that endangers it. Evelyn helps Ulysses understand the significance of the painting, with which she is familiar. Ulysses points out the beauty of a cloud, which she has never appreciated before. The familiar becomes new again, and the new becomes familiar.

The novel continues to play with these themes as Ulysses returns from war. The bombing of London has destroyed his childhood home and his father’s beloved workshop—they made globes, a process described in loving detail—but his friend’s pub has been preserved. There, he finds a job and, above it, a home. Everyone has been changed by the war, but they are still close, and so both new and familiar. Love remains love, if in a different form, and grief over everything that is lost remains as well. It is no accident that Ulysses eventually finds his way back to crafting beautiful and meticulous miniatures of the world that breaks his heart and teaches him to love, over and over again.

Still Life of course delves deeply into art as characters find themselves in everything from paintings to poetry to photography to music. The title comes from the heart of the still life, an artform paradoxically dedicated to transience and to the unseen hands that have arrayed the objects portrayed. Who is in the room with these objects? Who has painted them, and what has the artist changed in the process? What is the scene that has been arrested in the precise moment depicted by the work of art? What came before, and what will come after? What can make life stand still, even as we know we are hurtling towards an unknown future?

I want to write about the way this novel talks about women. I can’t face it. I can’t bring myself to explore the ways our hands shape the world around us, even as I try to face the deaths of so many whose rights are being taken from them. Abortion becomes legal in Italy during the course of the novel. I cried. I am crying now. So I will let you know that the exploration of gender in Still Life is nuanced and beautiful.

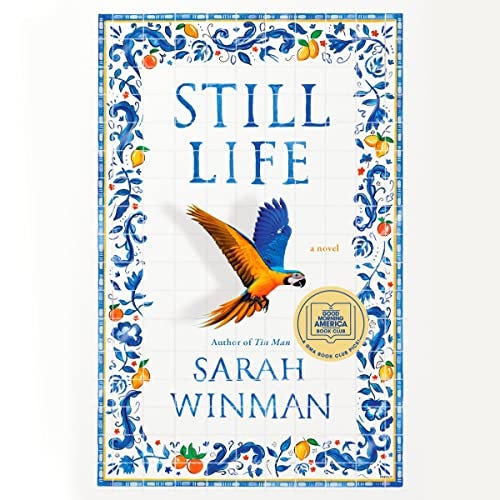

I will return now to those twin threads of grief and love, like the orange and blue of the book’s incredible cover art. Complementary colors, opposites on the wheel. If we never love, we never grieve. Grief is how love survives after its object is gone. I don’t know how to face the future after this loss. I look to the love that has always been there and will always survive. I don’t know how to feel hopeful, but I know beauty when I see it. If a city like Florence can survive so many disasters and still preserve the core of itself, so can I. Even if I can’t yet see how.

I put this on my MUST READ list. I share your grief, but I can feel myself returning to the kind of righteous anger that can (maybe) lead to some positive changes in the future. Being an historian gives me perspective (which I often struggle to lean into) that the slope of human progress is upward, though not continuously, with plenty of very dangerous dips. I hope this is not one of them. With you in this rather bleak time, A-M.